CPING Research Goals |

CONSORTIUM FOR PLANT INVASION GENOMICS (CPING)

Overarching Goals

Invasive species can occur through many mechanisms, can come from any taxon, and can be more or less problematic. Many species are introduced to new habitats and either fail to persist or become naturalized but not invasive. But why?

CPING seeks to find the common threads of plant invasions by investigating the genomics of five widespread invasive species with very different biologies. CPING focal species have invaded wetlands, forests, plains, and agricultural land. They are polyploid and diploid. They are flowering plants and non-flowering plants. They are native to Europe, Asia, and South America. By studying the genomics of this disparate taxa, our goal is not just to investigate the invasion dynamics of five different species. We aim to study the process of plant invasion broadly. |

Specific Aims

Colonization Dynamics -

For each focal species, we will infer the number and timing of introductions into the United States by sampling and sequencing genetic markers from individuals throughout the invaded range as well as from a time-series of herbarium-preserved specimens since the time of introduction. Combining these data with results from other species, we will identify the characteristics of invasive plants that correlate with multiple invasions. We will also assess the severity of genetic bottlenecks that occurred following each invasion. Gene Flow - Most focal species have the capacity to interbreed with native species, and each undergoes differing levels of admixture with either native plants or with other introduced populations of the invasive. Using sampling across the invaded range as well as herbarium specimens, we will assess when admixture typically occurs following introduction, whether invasive species primarily exchange genes with other introduced populations or with native taxa, and whether higher levels of admixture correlate with increased invasiveness. Adaptation - The role of adaptation on the invasion process is poorly understood. For the five focal species, we will a combination of common garden studies to assess fitness correlates with genetic variation, outlier analysis to look for genes under selection, and time-series studies of herbarium specimens to determine the timing of adaptation. Through these approaches, we will assess the genetic architecture of adaptation in invasives, determine of adaptive alleles were present in standing variation or arose de novo after introduction, and determine how quickly adaptive allelic elements and adaptive clines arose following introduction. |

Focal species

Microstegium vimineumJapanese stiltgrass, Microstegium vimineum, was introduced from Asia in 1919. It has spread to 24 states in the eastern and midwestern U.S., where it invades agricultural areas, secondary forests, riparian zones, and mesic open habitats. It crowds out native vegetation, changes ecosystem function, limits tree seedling recruitment, and changes abiotic and biotic soil attributes.

Salvinia molestaThe aquatic fern, giant salvinia (Salvinia molesta), is native to Brazil, but has been introduced in 22 countries. It is an allopentaploid and considered obligately asexual. Despite this, it is considered one of the 100 worst invasive species in the world (215) and is spreading rapidly along the U.S. Gulf Coast. Giant salvinia can double its dry weight in five days!

Trifolium repensWhite clover (Trifolium repens) is native to Eurasia but was introduced as a forage legume around the world in the 18th-19th centuries. It can now be

found invading feral fields, lawns, and grasslands on six continents. White clover has repeatedly evolved clines in cyanogenesis--the ability to produce hydrogen cyanide as an herbivory defense--in its native and invasive ranges. |

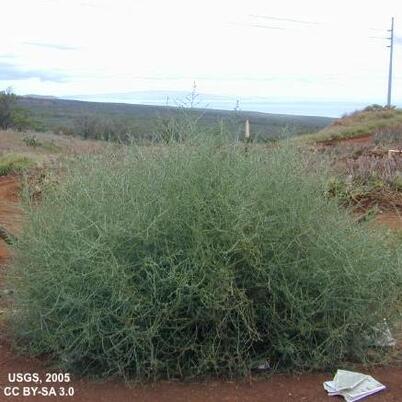

Salsola tragusRussian thistle, Salsola tragus, is common in arid landscapes across the U.S. and forms tumbleweeds upon senescence, allowing dispersal of hundreds of thousands of seeds over an expansive area. Russian thistle was introduced to North America in the 1870s. Following introduction, it spread nationwide in a matter of decades--one of the fastest plant invasions in U.S. history

Sorghum halepenseJohnsongrass, Sorghum halepense, is native to the Mediterranean but has been introduced onto every continent. Originally brought to the U.S. in the 1800s as a forage crop, Johnsongrass has become a ubiquitous agricultural pest and noxious weed in the southern U.S. It is an allotetrapoid formed from Sorghum propinquum and Sorghum bicolor, the source of cultivated sorghum.

|